Before radio nationalized musical types, and Dylan, Guthrie, Seeger and others involved in the american folk music revival of the fifties and sixties claimed the term to describe a particular lyrical style and approach to instrumentation, folk music was traditional music, and traditional music was regional music. Appalachian music was different from Cajun music was different from polka music was different from samba, but each in its own way was a kind of folk, literally "of the folk", and the variance in sound as one traveled through the country was rich and beautiful and vast, steeped in the ancestry of the local population, and played on the back porch or local dancehall as a way to reclaim the old country for the newer generation.

These days, of course, "folk music" usually means something entirely different. We see the term everywhere, with slashes and caveats, daily across the indie-populated blogosphere. But even as the term "folk" is being applied to a whole rising generation of acoustic indiekids, these different kinds of folk music seem to be moving back towards each other, a kind of musical genre reclamation.

Zydeco and Urban folk once used the term "folk" as if the other did not exist, but more and more often, one can find the two types played to overlapping crowds in adjacent tents at the same folk festival, if not one after another on the main stage. In my local library, Polka music rests more and more easily next to Dylan in the section labeled "folk". Some days, it is as if all popular American music is on the verge of falling into one of three broad categories: rock/pop/rap, classical, and folk/country.

The folk music tent gets larger every year. According to an unsourced statement in Wikipedia, in June of this year, the National Association of Recording Artists and Songwriters "announced a new Grammy category, Best Zydeco or Cajun Music Album, in its folk music field." Though here at Cover Lay Down we have chosen not to offer a "best of" list to end the year, in anticipation of this year's awards, and as a way to bring some swampy southern warmth to our short New England winter days, we bring you our first feature in a new series, Subgenre Coverfolk, in which we focus on a specific subset of the folkmusic sound.

According to

Wikipedia, Zydeco has its roots in the dual cultures and communities of the Louisiana bayou: French Creoles and African-american slaves. But Zydeco as a finite form did not truly emerge until after the Civil War, when many french-speaking creole and african-american communities of the deep swamp south moved towards Texas in the first half of the twentieth century to find work. There, the once-separatist creoles found themselves in common bond with free african-americans, and both peoples developed a need to congregate and celebrate their shared regional histories.

The music that they created to accompany themselves brought together instrumentation, lyrical elements, and other components of Creole music and african-american forms such as Jazz, Blues, and R&B. At first, just as folk music was still folk music after it lost its regionalism and began to describe a particular sound, this was just considered a new form of Creole music. But by the time Clifton Chenier and other began to introduce the sound to a generation of popular blues and R&B artists in the 1950s, they called it Zydeco.

The term "Zydeco" seems to be a corruption of african terms that mostly just means "dance", though its etymological origins are muddy as the delta -- other sources suggest it is derived from

les haricots, french for "the beans", a reference to the title of what many believe is the first mainstream Zydeco song.

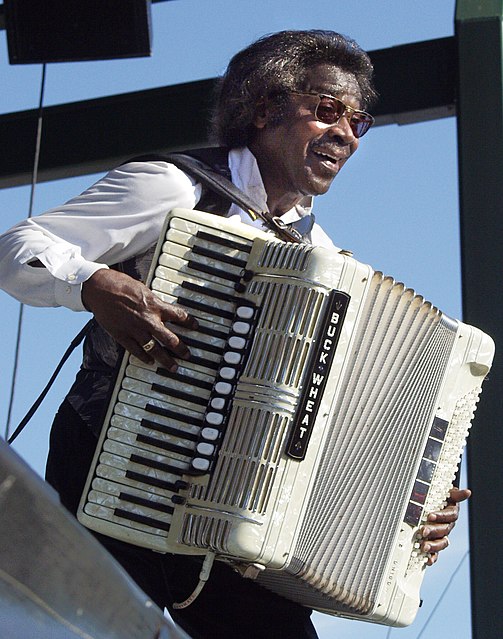

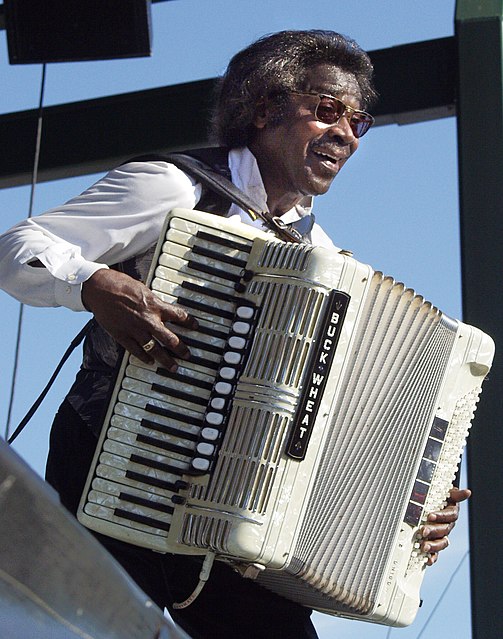

But the zydeco sound is clearly identifiable. In order to serve the cultural and emotional needs of its listeners, the instruments of Zydeco are typically those portable handhelds which need no amplification to be heard, and which will not wilt or lose their tone in heat and humidity: accordian as wearable piano; washboard as a drumset held close to the chest. Even the dance style of zydeco sprawls across the dancefloor, reclaiming land in a manner unlike the meeker and more static cajun waltzes and squares they evolved from. It may have absorbed some elements of rock and R&B over the years, but the Zydeco sound is still very much distinctive.

Today, some select covers from the reigning kings of modern Zydeco. You can catch these folks at the dance tent, late into the night, long after the mainstage folk or bluegrass festival acts have gone back to their hotels and song circles for the evening, and they're worth staying up for.

As always, album links above go to labels or artist homepages, not some huge and faceless conglomerate. Support niche labels, regional musicians, and small record shops, and keep the local alive.

As a nod to the continued evolution and cross-pollination of musical forms, today's bonus (re)coveredsongs come from O Cracker, Where Art Thou, "psychocajun slamgrass" group Leftover Salmon's collaboration with alt-rockers Cracker. Both songs are originally by Cracker.